None of us will ever forget the tragic news of the arson attack and fire at the Manchester Dogs Home on the evening of Thursday 11th September 2014. This senseless act of cruelty, and the fear and suffering those poor dogs must have gone through, is difficult to comprehend. Yet the tragedy did strike a chord in the Nation’s hearts. Within 24 hours over £1 million pounds was raised and the final figure was over £1.5 million, all through public donations.

3 years on, almost to the day, the UK Government Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs put out a press release on 30th September 2017, titled “Sentences for animal cruelty to increase tenfold to five years” (DEFRA, 2017).

In this press release, DEFRA state –

“There have been a number of recent shocking cases where courts have said they would have handed down longer sentences had they been available, including a case in April last year when a man bought a number of puppies just to brutally and systematically beat, choke and stab them to death. The new legislation will also enable courts to deal more effectively with ruthless gangs involved in organised dog fights.”

To be clear, this new legislation only applies to England. Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales are responsible for their own legislation.

Current English law already allows judges to impose unlimited fines and ban the offender from owning animals. However, the problem with this is that if the offender has limited financial resources, fines cannot be paid. Banning the offender from ownership of animals is equally pointless because ownership can be transferred in an instant to someone else, which gives the offender full access to very animals the law is there to protect.

What has changed in this amendment to the current law is that the maximum jail sentence that the courts can impose has increased from 6 months to 5 years. Remember that this fixed maximum sentence works on a sliding scale – starting at zero – based on the seriousness of the crime in terms of both the magnitude of the acts of cruelty inflicted on animal victims, the number of animals involved and the time scale over which the perpetrator had carried out these offences.

“We are a nation of animal lovers”, the British proudly claim, but in reality this is a very recent idea. In the eighteenth century the population paid little, if any regard to animal welfare and some positively revelled in being cruel to animals. The mistreatment of other species was so deeply engrained in the social fabric of society at this time that the British engaged in more ‘sporting activities’ that involved elements of animal cruelty than any other country in Europe. Of all the travellers to other countries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the English were singled out and reviled as the cruellest to non-human animals.

At this time non-human animals were colloquially known as ‘brutes’, and one Reverend Richard Dean lamented in 1768 that

“…brutes are perishing every day under the hands of barbarity, without mercy or warning. Starved as if hunger was no evil, mutilated as if they had no sense of pain and worked relentlessly without regard to extreme fatigue and suffering…”

In 1796, John Lawrence, a farmer and part-time philosopher, became so appalled by the relentless animal abuse he witnessed that he proclaimed that society had a collective obligation to protect animals against unnecessary suffering and proposed that this should become enshrined somehow in the legal fabric of the nation – that

“…the Rights of Beasts be formally acknowledged by the state…”.

This was a radical viewpoint at a time when the mentally and physically handicapped were treated with little regard and animal welfare and suffering was considered of no importance whatsoever.

It was not that ‘beasts’ were excluded from British law, far from it in fact. Domestic animals had for a long time been considered in law solely as property bestowing on the owner complete autonomy to do as he wished with his own processions. The only time that an extreme act of cruelty to an animal was significant in law was when it was considered in the context of damage to someone else’s property, and in this respect there was no shortage of legislation on the statute books, most of which related to game animals. Between 1670 and 1830 fifty new animal-related laws came into being, arguably the most infamous of which was the much feared ‘Black Act’ of 1723.

This act carried the death penalty for anyone engaged in any one of a raft of game animal related activities such as illegal deer hunting (regardless of whether a deer was actually caught or harmed), stealing wild hare from their warrens, or captive rabbits or hares from someone’s property, unlawful fishing in any river or pond (regardless of whether anything was actually caught) and unlawfully damaging or killing someone else’s cattle. When it came to the law relating to domestic animals in general, the owner of a killed or maimed ‘beast’ by another party could sue the perpetrator for damages, but it would have to be proven by the courts that there was malicious intent against the owner of the ‘beast’ by the accused.

Other minor laws aimed at banning specific public activities were also drafted, for example the empowering of constables on the beat to stop cock-throwing, a prevalent practice in the catholic calendar during lent (Shrovetide). Cock-throwing involved tethering a cock by one leg to a stake, the ‘players’ would then take it in turns to throw heavy sticks at the bird and the one who killed it won the ‘game’. Much of the cruelty meted out to animals, such as the beating of horses and driving and slaughtering of cattle, was commonplace, non-contentious and largely accepted. In short, the law was not concerned with the prevention of suffering in animals, but with maintaining public order and protecting property.

Other minor laws aimed at banning specific public activities were also drafted, for example the empowering of constables on the beat to stop cock-throwing, a prevalent practice in the catholic calendar during lent (Shrovetide). Cock-throwing involved tethering a cock by one leg to a stake, the ‘players’ would then take it in turns to throw heavy sticks at the bird and the one who killed it won the ‘game’. Much of the cruelty meted out to animals, such as the beating of horses and driving and slaughtering of cattle, was commonplace, non-contentious and largely accepted. In short, the law was not concerned with the prevention of suffering in animals, but with maintaining public order and protecting property.

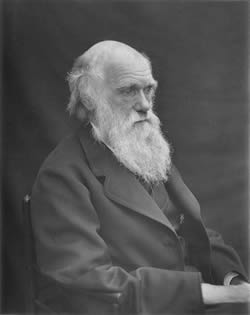

An enormous obstacle to any shift of prevailing attitudes towards animal welfare was religious doctrine. In 1859 Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species was published and it would be tempting to believe that this book must have had some influence on the public’s feelings with regard to animal cruelty. Not so. So profound, radical and contradictory to the traditional religious beliefs of the Victorians were the ideas presented in this book that Darwin’s theories about Man’s apparently mundane relationship with other species were missed completely. This was partly due, in fact, to Darwin’s own procrastination and reluctance to present his theories more clearly because of conflict with his own religious beliefs about Man’s special place in God’s creation plan and also fear of the negative repercussions from religious authorities and the general Christian Victorian society at large. Darwin carefully avoided including Man in his theories:

“I am in no doubt, after the most deliberate study and passionate judgement of which I am capable, that the view which most naturalists entertain, and in which I formerly entertained – that each species has been independently created – is erroneous…”

“…I am convinced that species are not immutable, but that those belonging to what are called the same genera are lineal descendants of some other and generally extinct species…”

He ended the book with the disclaimer

“Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

Nonetheless, the Bishop of Oxford lambasted Darwin and his theories as incompatible with the Biblical account of creation and the moral and spiritual representation of man as portrayed in Christian doctrine and encapsulated in the first chapter of the Bible, Genesis, that God created man in His image and gave him complete dominion over every living thing on earth, all of which had been created specifically for man to use as he pleased; man alone was endowed with a spiritual soul.

It is also worthy of note that Darwin was very much on the side of a movement against the rising anti-vivisection lobby during the second half of the nineteenth century. The deep-routed belief that non-human animals did not possess souls, and therefore by implication neither thoughts nor feelings, make it hardly surprising that attitudes toward the welfare of animals were so slow to change! Lest we believe that these hard-line Christian attitudes belong to the past, as recently as 1994 the Catholic Church reaffirmed its official doctrine, that animals are put on earth by God solely for the common good of humanity, no clarification added with regard to ‘animal souls’ or the potential of experiencing pain or suffering, although there was a concession this time round – that man owes them ‘kindness’.

It is also worthy of note that Darwin was very much on the side of a movement against the rising anti-vivisection lobby during the second half of the nineteenth century. The deep-routed belief that non-human animals did not possess souls, and therefore by implication neither thoughts nor feelings, make it hardly surprising that attitudes toward the welfare of animals were so slow to change! Lest we believe that these hard-line Christian attitudes belong to the past, as recently as 1994 the Catholic Church reaffirmed its official doctrine, that animals are put on earth by God solely for the common good of humanity, no clarification added with regard to ‘animal souls’ or the potential of experiencing pain or suffering, although there was a concession this time round – that man owes them ‘kindness’.

The 1600s and 1700s were both centuries of huge cultural change and scientific and intellectual thinking and rapidly developing understanding of the natural world. This ultimately led to the Age of Enlightenment, and part of this process was the gradual emergence of a movement towards universal human rights and the ideas surrounding utilitarianism, that the moral worth of someone’s behaviour is measured by the degree to which it provides happiness or pleasure to the greatest numbers. Discoveries such as the earth being part of the solar system and not the centre of the universe, exploration of hitherto unknown lands and the discovery of new species, and of fossils of extinct species by geologists all helped to break down the long-held beliefs based on man being ‘at the centre of the universe’.

The Age of Enlightenment also spawned a new breed of artists and philosophers whose work, sympathetic to nature and animals, infused the literature of the time. The church also underwent its own ‘little enlightenment’ with the break-away of less orthodox thinkers whose less rigorous interpretation of the Bible allowed for inclusion of non-human animals in God’s plan, bestowing a degree of humanity on their welfare in the process.

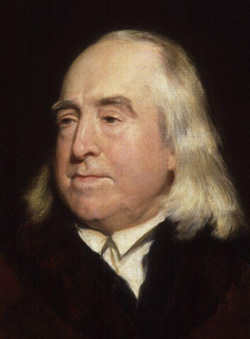

In 1789, Jeremy Bentham, the English lawyer and philosopher published his theories on the utilitarian idea, the most notable of which was that “Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure…”. As a legislator, Bentham was quick to point out that in terms of morality, as long as animals were subject to the whims of humans, their ‘happiness’ and ‘pain’ were relevant to the utilitarian ideal. This one idea was a hugely important first step towards the creation of animal welfare-specific legislation and opened the door to other thinkers of the day. For example, in 1792 Mary Wollstonecraft, the British writer and feminist, wrote that the teaching of compassion to animals should be on the school curriculum because children who grow up with a disregard to animals are more likely to become wife and child abusers as adults.

It is interesting to note that in 2003, the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, the governing body for veterinary surgeons in the United Kingdom, added a new section to the Guide to Professional Conduct entitled ‘Animal abuse, child abuse, domestic violence’. This new piece of legislation essentially allows a veterinarian to break the confidentiality agreement he or she has with a client if they belief that the account given by the client as to how the animal being presented sustained its injuries is inconsistent with those injuries and cannot be reasonably accounted for. In such a case, the veterinarian has a duty to report the matter to the relevant authorities. This addition to the Guide came about as a direct result of the Governments re-discovery of the link between animal abuse and domestic violence and child abuse pointed out over 200 years earlier.

Between 1800 and 1822 various attempts were made to enshrine some of Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian ideas into British law. One notable attempt was that of Thomas Erskine in 1809. Erskine’s Cruelty to Animals Bill was clever because it avoided the question of whether or not non-human animals had souls, and therefore whether or not they could think and feel, in favour of comparing similarities to human behaviour to feeling pleasure or to the infliction of pain. In this regard the Bill was human-centric in its interpretation.

Between 1800 and 1822 various attempts were made to enshrine some of Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian ideas into British law. One notable attempt was that of Thomas Erskine in 1809. Erskine’s Cruelty to Animals Bill was clever because it avoided the question of whether or not non-human animals had souls, and therefore whether or not they could think and feel, in favour of comparing similarities to human behaviour to feeling pleasure or to the infliction of pain. In this regard the Bill was human-centric in its interpretation.

This was because it was not aimed at any specific activity or demographic group, and was broad in its scope in making it an offence for anyone, including the owner, unnecessarily to abuse a horse, a cow, a pig or a sheep. The Bill made it through the House of Lords, but sadly failed to get through the Commons.

“The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being?” Jeremey Bentham (1789) – An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation.

In 1822, almost twenty five years after Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian theory the first piece of animal welfare-specific law make it onto the British statute books. Richard Martin drafted the Bill with the assistance of Thomas Erskine which became An Act to Prevent the Cruel and Improper Treatment of Cattle. Between 1822 and 1826, Martin repeatedly tried to broaden the Bill to include cats, dogs, monkeys and other species, but sadly none of these amendments ever made it into law. However, Martin remained an influential figure in the Commons on account of his vast knowledge on animal welfare issues.

Of course, it is one thing to pass a law to protect animal welfare, quite another to enforce it. Using the legislation to bring prosecutions against individuals was left to private citizens. To protect his Bill from falling into obsolescence, Martin brought the first prosecutions for animal cruelty to court himself, and it is interesting to note that on most occasions when the prosecution was successful, he paid the guilty party’s fine himself, usually of the order of ten shillings.

Martin brought the world’s first known conviction for cruelty to animals against Bill Burns for beating his donkey.

Coincidently, at around the same time in 1824, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) was established and managed to prosecute 149 cases successfully in its first year. The society was badly managed and poorly funded, however and all but went bankrupt on several occasions in its early days. The SPCA survived and in 1840 became the

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) through the patronage of Queen Victoria.

This was hugely important to the perception of Victorian society on animal welfare and was instrumental in the manner in which animals became legally protected over the coming years. This was most notable in the way animals were slaughtered for meat which, until then had been nothing short of barbaric, and the banning of some blood sports such as bull-baiting and badger-baiting. It is a sobering thought indeed that at this time in the history of animal welfare law, animals had better legal protection than children – it took another sixty years before the National Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) came into being.

In 1849 Martin’s Bill finally matured into The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1849, the scope of which extended across all animal species, and included birds. A key modification to this Act was that it was redefined so the prosecution only had to establish that what the defendant did to an animal was indeed cruel. Previously, the law was required to establish that the defendant had intentionally and knowingly committed the offence – much more difficult to prove.

In 1849 Martin’s Bill finally matured into The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1849, the scope of which extended across all animal species, and included birds. A key modification to this Act was that it was redefined so the prosecution only had to establish that what the defendant did to an animal was indeed cruel. Previously, the law was required to establish that the defendant had intentionally and knowingly committed the offence – much more difficult to prove.

Another significant addition to the Act was that liability extended to third parties so making employers responsible for what their workers were doing. There was also a clause in this Bill relating to transporting animals in vehicles, which was the seed of what has now become a raft of complex European legislation relating to transport of livestock. Along with all this new-found British concern for animal welfare came the foundation of Battersea Dogs Home in London, the first of its kind, in 1867.

As vigorous as the new-found British compassion for animals was, it did not extend to those used in vivisection. The vivisection story is a long and highly contentious one, but in 1876 The Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 came into being as a very much watered-down version of what an embryonic ‘Anti-Vivisection Society’ had wanted. The Act was reviewed by two Royal Commissions (the first when it was drafted, the second in 1906), and both concluded that it did not need changing. However it was superseded by The Protection of Animals Act 1911.

The treatment of (sick) animals was an obvious part of their welfare and this became the responsibility of the farrier. In 1791 the Veterinary College in London (later to become the Royal Veterinary College) was established, followed in 1820 by the Edinburgh College (that became the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies). Despite the establishment of these places of study, ‘Veterinary Medicine’, remained archaic, employing practices such as bleeding and blistering with hot irons as part of almost every ‘treatment’. In 1844 the work of ‘veterinary practitioners’ was granted a Royal Charter and the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (RCVS) was formed, establishing a recognised Veterinary Profession. Members were registered by the College and could then call themselves Veterinary Surgeons.

The problem with the RCVS is that it had no legal powers to govern the practising standards of its members, which varied enormously, despite the introduction of a four-year education course and written examinations. In 1881, the Veterinary Surgeons Act came into being that made it a legal requirement that only registered members of the RCVS could practice veterinary medicine, and by removing wayward or incompetent members from the register, the RCVS had a mechanism for maintaining standards and giving the public confidence in the now well established Veterinary Profession.

With the establishment of veterinary journals and modernisation of the veterinary curriculum taught at the colleges, what was formally ‘veterinary art’, became the much more respectable ‘veterinary science’.

In 1911, after much deliberation, The Protection of Animals Act 1911 came into being to update and combine the 1876 Cruelty to Animals Act and the 1900 Wild Animals in Captivity Protection Act. The 1911 Act included refinements such as tightening up procedures in knackers yards and slaughter houses, the banning of the use of dogs to pull carts and more powers of confiscation for the protection of the animal. This Protection of Animals Act 1911 remained the cornerstone of British animal welfare legislation right up until the 6th April 2007 when The Animal Welfare Act 2006 came into force.

So, in 2017 where are we now?

It seems as though some things have changed for the better, while some things have not.

There are still 126,176 dogs being abandoned every year, that’s a staggering 345 dogs every day, the worst in over a decade. Just 1 in 3 pet owners are aware of the Animal Welfare Act 2006 and their five basic legal obligations for their pets’ welfare (the ‘five freedoms’). 42% of prospective pet owners consider the internet a legitimate place to buy a pet while 24% would consider a puppy farm puppy. A staggering 23% did no research whatsoever on the animal before going out and buying their pet. 68% of children have pets in the household but just 7% are aware of their five basic needs. Only 16% of children have been taught anything about animal welfare at school (PDSA, 2014). The fire at the Manchester Dogs home was started by a 15 year-old boy. In the Governments review of the National Curriculum for England it is absolutely essential that basic animal welfare becomes part of what children are taught, starting in primary school classes and extending on into the core curriculum of the biological sciences.

The link between animal abuse and child abuse has been well understood for decades (references available on request). It is already an integral part of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons ‘Code of Conduct’ for veterinarians (RCVS, 2017). This new legislation is a small step in the right direction, but the time it has taken for the government to take premeditated animal abuse seriously is disappointing.

The real question is –

WHY HAS IT TAKEN SO LONG?

The government is busy on so many fronts.

But does this really mean that – ‘this nation of animal lovers’ is left tip-toeing our way towards better animal welfare legislation indefinitely?

© copyright Robert Falconer-Tayloe, 2017

This article is an original work and is subject to copyright. You may create a link to this article on another website or in a document back to this web page. You may not copy this article in whole or in part onto another web page or document without permission of the author. Email enquiries to robertft@emotions-r-us.com.

Images used in this article

1. Badger baiting. By Henry Thomas Alken [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

2. Charles Darwin. By J. Cameron (Unknown) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

3. Jeremy Bentham. Henry William Pickersgill [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

4. Trial of Billy Burns. See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Selected References

DEFRA, 2017. Sentences for animal cruelty to increase tenfold to five years. http://bit.ly/2kcxLkX. Accessed 30/09/2017.

PDSA, 2014. Animal Wellbeing Report (PAW). http://bit.ly/2kc0xCm. Accessed 30/09/2017.

RCVS, 2017, 14. Client confidentiality. http://bit.ly/2xNId7n. Accessed 30/09/2017.